Category: Family

-

Stewards of the Story

Read More: Stewards of the StoryLast night, I was working with my seven year-old daughter on a Bible verse that she is trying to memorize. The verse spoke about the “fear of God” and we had a good discussion about the definition of the word “fear” in that context. While that alone is a whole other discussion, the point I…

-

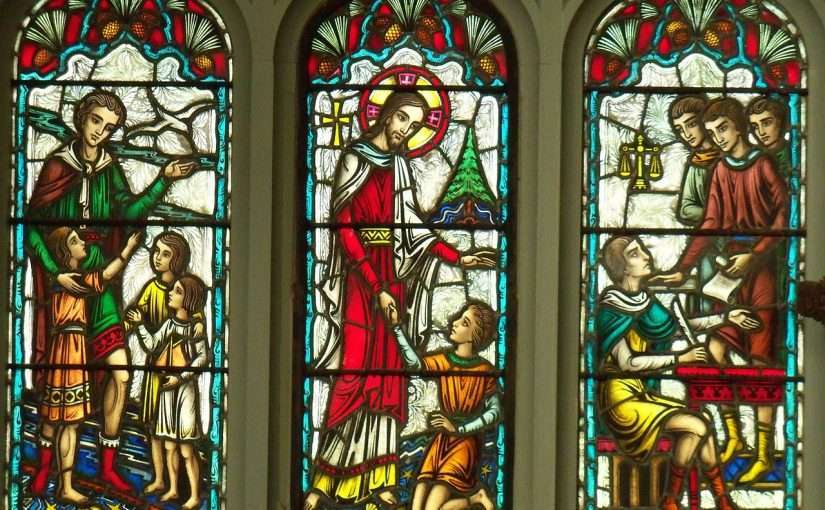

The Idea of Invitation in Worship

Read More: The Idea of Invitation in Worship“Let the little children come to me.” – Jesus of Nazareth This past Sunday was a snow day in our part of the country. Most churches closed due to weather. When my wife, daughter, and I made our way downstairs to make some breakfast together, my wife suggested that we have a family devotional time.…

-

Do you do Santa Claus?

Read More: Do you do Santa Claus?This is a common question I hear parents asking one another at Christmas time. The question comes from different perspectives and experiences that people have had with the story, tradition, and character of that jolly man, Santa. We’ve all heard stories of the proverbial thirteen year-old kid (or older) who finds out from their friends…

Search

Popular Posts

-

“Holy Fools”: Exploring the Journey of Calling for Christian Variety Performers

I am happy to announce that my PhD dissertation has been published to ProQuest, an academic database for published research. I have made the dissertation open source, which means anyone anywhere can access the full content free of charge. Here is the full dissertation: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/holy-fools-exploring-journey-calling-christian/docview/2622316783/se-2 Please share far and wide. I am very much excited…

-

The Easiest Large Group Game Ever

This is probably the easiest large group game ever invented. If you can think of an easier one, please let me know in the comments. Heads or Tails! This game of heads or tails involves EVERYONE in your large group. It is actually better the larger the group gets. There is an elimination factor to…

-

Book Release! Incredibly Bad Dad Jokes

I have been writing down my original Dad jokes for several years now, but recently they dramatically increased. While the past five months of my life have been the toughest for me as a Dad (with Annie’s medical crisis), the Dad jokes actually came out in full force during this season. You see, in my…

-

A Children’s Ministry Poem

From the mouths of children come questions galore about heaven and angels and Satan and more. They speak what their hearts say without holding back, so the wonder of God is something they never lack. Oh God, who are you? Who inspires the minds of little ones many, so that they may find this Jesus…

-

Joyner Family Christmas 2024 Update

Merry Christmas from the Joyners! Here’s a little bit of our life this past year. We hope and pray the Lord’s peace and blessing over you this Advent season. D – Our little guy is now 5 years old! This year he played Tee Ball in the Spring and started soccer this past Fall when…